The Iron Goat Trail offers hikers a unique journey through both stunning Pacific Northwest scenery and fascinating railroad history. Winding along the former route of the Great Northern Railway near Stevens Pass in Washington, this trail combines natural beauty with powerful historical significance. The trail is named after the mountain goat symbol of the Great Northern Railway and marks the site of the deadliest avalanche in U.S. history, which claimed 96 lives when it swept two trains off the tracks at Wellington in 1910.

Today’s visitors can explore the 6-mile historic path featuring restored tunnels, snowsheds, and interpretive signs that tell the story of early 20th-century railroad engineering. The trail itself has its own interesting history, opening to the public on October 2, 1993, after dedicated volunteers and the U.S. Forest Service transformed the abandoned railway into the accessible hiking trail enjoyed today. Walking the Iron Goat Trail gives hikers a chance to step back in time while enjoying mountain views, lush forests, and the echoes of steam locomotives that once labored through these peaks.

Get a discount of 15% to 70% on accommodation near Iron Goat Trail! Look for deals here:

Iron Goat Trail Hotels, Apartments, B&Bs

The Origins of the Iron Goat Trail

The Iron Goat Trail follows a historic railway route through the Cascade Mountains, with a past marked by engineering triumphs and tragedy. This scenic hiking path preserves an important piece of Washington’s transportation history.

Great Northern Railway

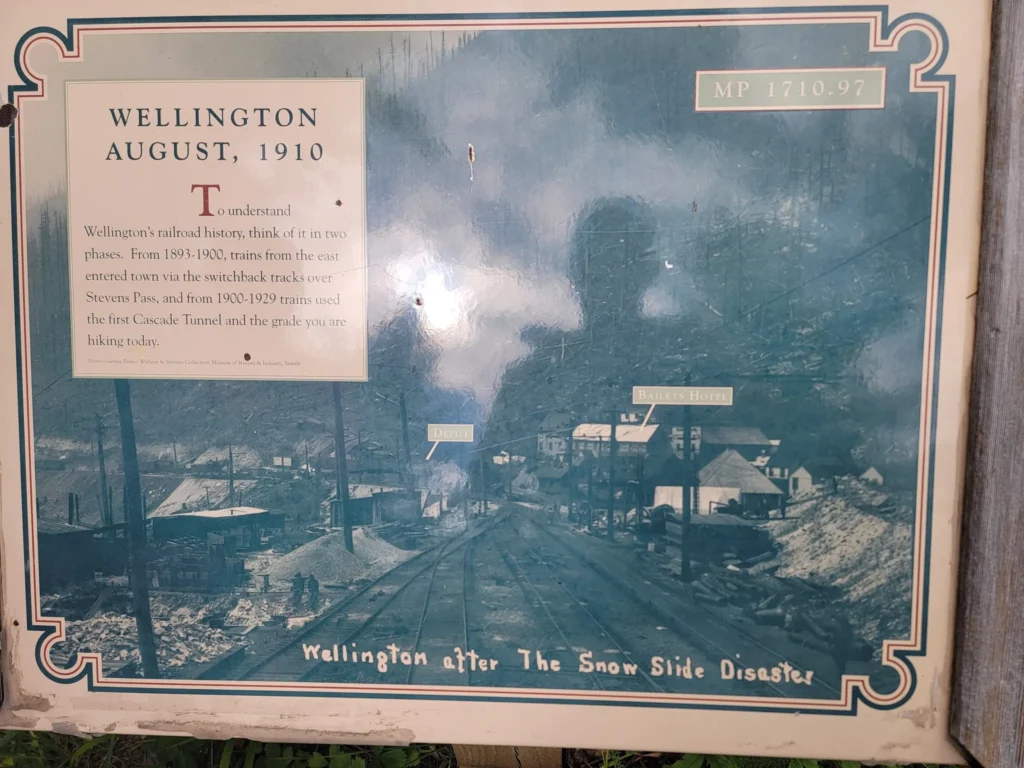

The Iron Goat Trail traces the history of the Great Northern Railway’s original route through the Cascade Mountains. Built in the 1890s, this railway line was crucial for connecting Seattle and Puget Sound to the eastern United States.

The Great Northern Railway, founded by railroad magnate James J. Hill, sought to establish the most efficient northern transcontinental route. The company faced immense challenges cutting through the rugged Cascades.

Engineers designed a winding path with steep grades and sharp curves to navigate the mountains. This original route required helper engines to push trains up the 2.2% grade at Stevens Pass.

The railway line became known for its treacherous winter conditions, with heavy snowfall and avalanche dangers threatening operations each year.

John F. Stevens’ Role

John F. Stevens, the chief engineer for the Great Northern Railway, played a critical role in developing the mountain passage. His exploration of the Cascades in winter led to the discovery of the pass that now bears his name.

Stevens braved harsh conditions in December 1890, traveling on snowshoes to locate a suitable railway route. His determination and engineering expertise made the mountain crossing possible.

The difficulties Stevens encountered during his explorations highlighted the challenges the railway would face. He developed innovative solutions including massive snow sheds to protect the tracks from avalanches.

Stevens’ contribution to American railroading extended beyond this route, as he later worked on the Panama Canal project.

The Development of Stevens Pass

Stevens Pass quickly became a vital transportation corridor through the Cascades after the railway’s completion in 1893. The original route included numerous timber snow sheds and tunnels to protect trains from the harsh mountain elements.

The pass gained tragic fame after the 1910 Wellington Disaster, when an avalanche swept two trains off the tracks, killing 96 people. This remains one of America’s deadliest avalanche disasters.

After the tragedy, the Great Northern Railway built longer, more protective snow sheds and eventually constructed the 7.8-mile Cascade Tunnel to avoid the most dangerous sections of the original route.

When the 8-mile Cascade tunnel opened in 1929, the original Stevens Pass route was abandoned. The historic rail grade remained largely forgotten until preservation efforts began decades later.

Image Source – https://www.cascadeloop.com/wellington-train-disaster

Tragedy and Triumph

The Iron Goat Trail preserves the memory of both devastating railroad disasters and remarkable human perseverance in the challenging Cascade Mountains.

The Wellington Avalanche Disaster

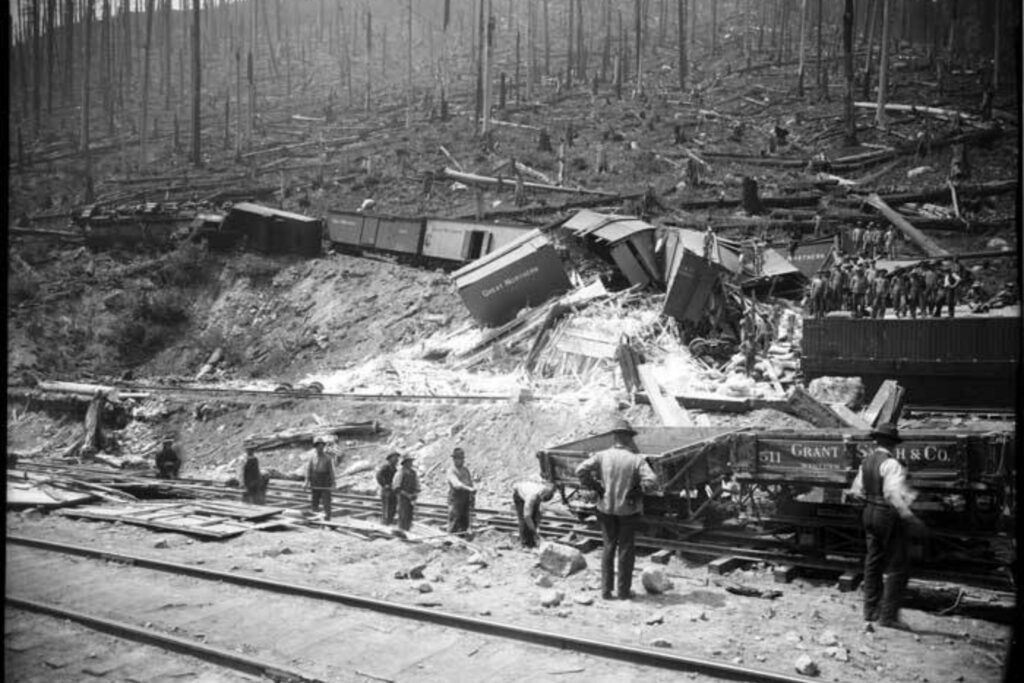

On March 1, 1910, one of the worst train disasters in U.S. history struck near Stevens Pass. Two Great Northern Railway trains—a passenger train called the Spokane Express and a mail train—had been stranded for days at Wellington due to heavy snowfall blocking the tracks.

In the early morning hours, a massive avalanche thundered down Windy Mountain. The powerful snow slide swept both trains off the tracks and down the mountainside, claiming 96 lives.

The disaster happened after a storm had dumped feet of snow on the mountains for nine days straight. Then, warm rain and lightning triggered the deadly avalanche.

The railway had built snow sheds to protect many sections of track, but the Wellington station area remained exposed to the mountain’s fury.

Railroad Disasters in the Cascades

The Wellington disaster wasn’t the only challenge faced by the Great Northern Railway. The original route through Stevens Pass tested both engineering capabilities and human endurance.

Before the 8-mile Cascade tunnel opened in 1929, trains navigated a treacherous switchback system with steep grades. This original route is what visitors can explore today on the Iron Goat Trail.

Winter conditions regularly threatened operations:

- Frequent avalanches blocked tracks

- Snow accumulations reached 40+ feet

- Rotary snowplows worked constantly

- Delays of days or weeks were common

The railway also faced tunnel disasters, including fires and asphyxiations from coal-burning locomotives in the original shorter tunnels.

Response and Recovery

After the Wellington disaster, the Great Northern Railway quickly renamed the site “Tye” to distance itself from the tragedy. They also constructed more protective snow sheds along vulnerable sections of the route.

The railroad eventually abandoned this original route in favor of the longer Cascade Tunnel built lower on the mountainside, which significantly reduced avalanche risks.

Decades later, volunteers led by Ruth Ittner worked to create the Iron Goat Trail along the historic rail bed. Their efforts preserved this important piece of railroad history.

The first segment of the trail opened in October 1993, and today hikers can explore tunnels, snow sheds, and interpretive signs telling the story of railroad triumph and tragedy.

The trail offers a peaceful reflection space to honor those who lost their lives while showcasing the impressive engineering feats required to construct a railroad through the challenging Cascade Mountains. Some people even claim that the trail is haunted as a result of the accident.

Engineering Marvels

The Iron Goat Trail follows the path of one of America’s most impressive railroad engineering achievements. The Great Northern Railway overcame the harsh winter conditions of Stevens Pass through remarkable structural solutions that still amaze visitors today.

Tunnels and Snow Sheds

The harsh winter conditions at Stevens Pass presented deadly challenges for the Great Northern Railway. Engineers designed impressive structures to protect trains from avalanches. The most notable was the Cascade Tunnel, which allowed trains to pass safely through the mountains rather than over them.

Snow sheds were another brilliant solution. These wooden structures were built over the tracks in avalanche-prone areas. They were designed to let snow slide over the top while trains passed safely beneath. Many remnants of these protective structures can still be seen while hiking the trail.

Hikers can explore these engineering relics firsthand. The trail passes through tunnel remnants and alongside deteriorating snowsheds that tell the story of railroad innovation.

Technological Innovations

The Great Northern Railway introduced several technological innovations to conquer Stevens Pass. The railway was considered an engineering marvel of its era, carving a path through landscapes previously thought impassable.

Switch-back routes allowed trains to zigzag up steep inclines. This clever design solution helped trains climb the challenging mountain grades that would otherwise be impossible.

Electric locomotives were eventually introduced to tackle the pass more efficiently. This forward-thinking change reduced smoke in the tunnels and provided more consistent power for the steep climbs.

Communication systems were also revolutionary for their time. Telegraph lines allowed stations to coordinate train movements through the dangerous mountain passes, improving safety and efficiency.

Visitors hiking the Iron Goat Trail today can appreciate these innovations that made the seemingly impossible railroad route a reality.

The Trail Today

The Iron Goat Trail has transformed from abandoned railroad tracks into a popular hiking destination in the Pacific Northwest. Today it offers visitors a blend of natural beauty and railroad history through careful maintenance and thoughtful improvements.

Revival and Maintenance

The Iron Goat Trail officially opened on October 2, 1993, after receiving a $99,000 state grant that funded construction of a 2.6-mile section along the historic rail route. This revival breathed new life into the abandoned Great Northern Railway corridor, preserving an important piece of Pacific Northwest history.

Today, the trail features well-maintained paths that follow the former rail grade and snow sheds dating back to before the 8-mile Cascade tunnel opened in 1929. These paths have been carefully restored to provide safe access for hikers of all abilities.

Interpretive signs placed throughout the trail help visitors understand the historical significance of various features they encounter. These signs tell the story of the railroad’s construction, operation, and eventual abandonment.

Volunteers and The U.S. Forest Service

The trail exists largely thanks to the dedicated efforts of Volunteers for Outdoor Washington, who work in partnership with the U.S. Forest Service. These organizations collaborate to ensure the trail remains accessible and educational for visitors.

Volunteer teams conduct regular maintenance work including clearing brush, repairing trail surfaces, and updating informational displays. Their commitment helps preserve both the natural environment and historical elements along the route.

The U.S. Forest Service provides oversight and resources for larger maintenance projects. They also help coordinate safety measures, especially around potentially dangerous historical structures like old tunnels and snow sheds.

Hiking the Iron Goat Trail

The Iron Goat Trail offers an easy hiking experience accessible to many skill levels. The trail system follows multiple sections of the former railway grade, with the main trail stretching approximately six miles one-way.

Hikers can choose between upper and lower portions of the trail, each offering different perspectives of the surrounding mountains and historical features. At Windy Point, just a quarter-mile detour offers spectacular views of Stevens Pass, surrounding peaks, and the current railroad line.

The trail is known for its rich natural environment, featuring lush forests and seasonal wildflowers. Wildlife sightings are common, adding to the appeal for nature enthusiasts.

Many visitors are drawn to the trail’s historical significance, particularly around Wellington (now Tye), where a devastating avalanche in 1910 claimed many lives. This tragic history makes the peaceful trail today all the more poignant.

Natural Splendor

The Iron Goat Trail winds through some of Washington’s most remarkable wilderness, showcasing the diverse ecosystems of the western Cascades. Visitors encounter a variety of wildlife and witness dramatic geological features shaped by the area’s volcanic past.

Flora and Fauna

The trail corridor features a rich tapestry of plant life typical of the western Cascades. Dense forests of western hemlock, Douglas fir, and western red cedar create a lush canopy along much of the route. In spring and summer, wildflowers including trillium, columbine, and beargrass dot the forest floor.

Wildlife viewing opportunities abound for patient hikers. The trail’s namesake mountain goat can occasionally be spotted on higher rocky outcroppings. Black bears forage for berries in summer months, while smaller mammals like marmots and pikas dart among the rocks.

Birdwatchers will appreciate the variety of species present, from soaring raptors to tiny chickadees flitting through the understory. The dense forest provides ideal habitat for woodpeckers, whose drumming echoes through the trees.

Geographical Features

The trail traverses a dramatic landscape shaped by volcanic forces and glacial action. The Cascade Mountains formed through tectonic activity, creating the rugged terrain visible today. Several sections offer breathtaking views of nearby peaks and valleys when weather permits.

A notable feature near the trail is a natural hot spring, located about three miles east of Scenic. This geothermal feature stands as evidence of the region’s volcanic origins and the powerful forces still at work beneath the surface.

Water features punctuate the journey, with seasonal waterfalls cascading down steep slopes after heavy rains or during snowmelt. These dynamic features change dramatically through the seasons, from raging torrents to delicate trickles.

The area’s history of natural disasters, particularly avalanches, has shaped both the human story and physical landscape of the trail. The very slopes that create such stunning beauty also present dangers during winter months.

Connecting Communities

The Iron Goat Trail not only preserves an important piece of railroad history but also links towns and communities that once relied on the Great Northern Railway. This historic route transformed the Pacific Northwest landscape and continues to connect people to a shared heritage.

Skykomish to Wellington

The stretch of rail line from Skykomish to Wellington represents a crucial link in the Great Northern Railway’s push through the Cascades. This challenging section required massive engineering efforts to connect these small mountain communities. Trains struggled up steep grades and through harsh winter conditions to maintain this vital connection.

When the first segment of the Iron Goat Trail opened in October 1993, it began restoring this historic connection. Today, visitors starting at the Martin Creek Trailhead can follow the same route trains once took.

The trail’s accessibility from Highway 2 makes it easy for modern travelers to experience this historic connection between communities. Interpretive signs along the way help hikers understand the immense challenges faced by early railroad workers.

The Impact on Local Towns

The Great Northern Railway transformed small mountain settlements into bustling railroad towns. Skykomish became a division point where trains added helper engines to tackle the steep grade toward Wellington. The towns grew as workers and their families settled in these once-remote areas.

The famous “last spike” connecting the eastern and western tracks was driven about one mile west of Martin Creek on January 6, 1893. This momentous event linked communities across Washington state and beyond, enabling economic growth throughout the Pacific Northwest.

When the original high-line route was abandoned in 1929 for the current lower Cascade Tunnel, many of these communities faced decline. The Iron Goat Trail project, championed by dedicated volunteers like Ruth Ittner, has helped reconnect people to this history.

Today, these towns benefit from heritage tourism as visitors explore the trail and learn about the region’s rich railroad past. See our list of nearby hotels, vacation rentals, and BnBs; as well as our list of other things to do in the area.

Get a discount of 15% to 70% on accommodation near Iron Goat Trail! Look for deals here:

Iron Goat Trail Hotels, Apartments, B&Bs